An edited version of talk first given at a shul in Nottingham about red Jews.

This presentation is a slightly edited version of one that was delivered at the Nottingham Progressive Jewish Congregation’s “Educational Day”, on 24 November 2013. It was written to be accessible to people without much prior knowledge of the subject, so may be a little light for anyone who has studied the history more deeply. It is also unashamedly politically biased: I consider myself a broadly-libertarian, “unorthodox Trotskyist”, an anti-Stalinist in the tradition of Max Shachtman, Hal Draper, and Phyllis Jacobson.

The slides referred to in the text are from a very poorly-designed PowerPoint presentation which accompanied the talk. That can be accessed here, but I’ve added in photos which hopefully means you won’t have to suffer the slideshow.

The presentation’s exclusive focus on Ashkenazi Jews is reflective only of the limitations of my own knowledge. I hope Jewdas readers find it at least somewhat informative, and maybe useful.

(Daniel Randall, 2014. Daniel is a transport worker in London, an activist in the RMT union, and a member of Workers’ Liberty. He also performs hip-hop and spoken-word poetry as The Ruby Kid.)

[SLIDE ONE – CHURCHILL QUOTE]

“From the days of […] Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky (Russia), Bela Kun (Hungary), Rosa Luxemburg (Germany), and Emma Goldman (United States), this world-wide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilization and for the reconstitution of society on the basis of arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality, has been steadily growing […]There is no need to exaggerate the part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution, by these international and for the most part atheistical Jews, it is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from the Jewish leaders.”

This is a quote of which I am excessively proud. It comes from Winston Churchill. It offers a succinct exposition of one of the recurrent tropes of 20th century anti-Semitism – that Bolshevism (or revolutionary anti-capitalist politics more widely, because Churchill mentions Emma Goldman, who was an anarchist rather than a Bolshevik), was a Jewish conspiracy, predominantly animated and controlled by Jews.

The reality was a little more complex – of the Bolshevik party’s 10,000 members in February 1917, less than 4% were Jewish. However, it is an undeniable fact that, in a particular period of European history, hundreds of thousands of mainly working-class Jewish people were involved in revolutionary politics – as activists, as organisers, as thinkers, and as theorists. Thriving and diverse traditions of revolutionary politics existed in the Jewish communities of Europe and America, from the mid-1800s up until the Second World War. Whatever your political views, and whether you think these ideas represent a living tradition, as I do, or merely a historical artefact, engagement with and production of revolutionary political thought and action is undeniably a huge part of the history and experience of the Jewish people, and is therefore, I believe, well worthy of study and discussion.

My talk is going to focus on a particular period of history – roughly the mid-1800s up to the 1930s – and almost exclusively on a particular group of Jews – Ashkenazi, Eastern European Jews. That period is a significant focus because it’s the one in which can talk about discrete Jewish revolutionary movements, and mass involvement of Jewish workers in revolutionary movements in general, before the infrastructure of European Jewish life, including distinct Jewish revolutionary political organisation, is smashed to pieces by Nazism.

It is in this period that a mass of Jewish people were thrown together by Russian imperialism in the “Pale of Settlement”, which included parts of what are now Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, and Moldova. That mass numbered five million at its height, and living conditions were characterised by extreme poverty. Jews were harried by pogroms, and being rapidly proletarianised, but in an uneven way that left much artisanal labour on the fringes of capitalist production intact. That historical moment, and those experiences – forced onto the fringes of developing society, in some senses excluded from but also convulsed by its economic development – are the key seedbeds for our topic today and the best laboratory for studying it.

What was the real extent of Jewish involvement in revolutionary politics in this period? The Bolshevik Central Committee of 1918 was one third Jewish, and 13% of the delegates to its 1921 Congress were Jewish. There was significant involvement predating and beyond the Bolsheviks, too. The General Jewish Labour Bund, an organisation we’ll be revisiting later on, claimed 3,500 members upon its founding in 1897, a figure which exploded to nearly 40,000 less than 10 years later.

Why did so many Jews become revolutionaries? I’m going to posit two possible answers to that question, which, for reasons of time, I will have to relate in very broad terms which will probably do little to justice to exponents of either.

The first view is that there is something inherent in Judaism, either in terms of its theology, its religious doctrine, or what we might call its religio-philosophical principles, that inclines us towards radical, democratic, social-justice-based, and collectivist politics. Radical rabbis like Michael Lerner are advocates of this view, or views like it.

The other view is that the material historical experience of Jews, as a people who have experience systematic brutalisation and oppression throughout much of our history, particularly compels Jews towards radical and revolutionary politics as a response, and resistance, to that experience of oppression.

I don’t think it will be possible in the time we have to engage in a full exploration of that question. We can only scratch the surface. Briefly, I’ll say that neither view quite hits the mark.

Rather than trying to explore that question in depth, my main intention with this talk is to introduce you to some characters from Jewish revolutionary history with whom you may not be familiar, and hopefully inspire you to go away and read more about them, the political milieus they inhabited, and the ideas which animated their activity.

Revolutionaries of all backgrounds in this period, and later, wrote and debated extensively on “the Jewish question” – how to understand this mass of people, a nation but not a nation, and whether to advocate various forms of national or cultural autonomy, assimilation, or some combination of both. Much of the work of the people we’re about to meet was concerned with this question and attempts to resolve it in various different ways. This debate is, in my view, quite intrinsically bound up with the question of why so many Jews became revolutionaries.

Whatever side one takes on those questions, it is undeniable that there is a rich seam of revolutionary ideas and activity in our collective history as a people. It is a seam with which I think we should reconnect — not merely as a historical curio, but as a guide to political action today. If my talk today edges anyone even remotely closer to doing that, I’ll consider it to have been a success.

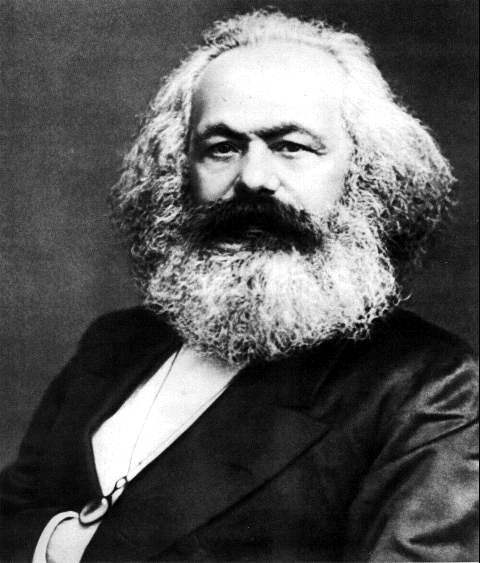

[SLIDE TWO: KARL MARX]

[SLIDE TWO: KARL MARX]

Karl Marx’s lineage is very Jewish indeed. His forebears were the rabbis of Trier right up until his grandfather, Meier Halevi Marx. But his father, Herschel, ruined it all by becoming an avowed secularist. He even went so far as to change his name to Heinrich and convert to Protestantism to escape anti-Jewish repression and legal discrimination.

In a sense, Marx isn’t a particularly interesting figure to dwell on here because his milieu was not a particularly “Jewish” one. It was the milieu of the European university and, later, the German, French, and British labour movements of the 1850s, 60s, and 70s. Marx is a “Jewish revolutionary” only in the sense of his ethnic origin.

But I wanted to start off with him because he is the most significant pioneer of revolutionary politics as we understand them today, and also because his own writing on “the Jewish question” are the source of great controversy.

His 1843 work “On the Jewish Question” recycles, it has been argued, anti-Semitic stereotypes of Jewish usurers and Jewish financiers, and Jew as a financial-economic functionary. Its language is problematic, but I think it’s a valuable work that tells us something about Jewish experience and which can help us work towards answering the question of what it is in that experience which compelled so many Jews to draw revolutionary conclusions.

The “economic-Jew” stereotype stems from the forced duality of Jewish experience in relation to the rise of capitalism. We were at one liminal and integral to it. Jews represented an incipient mercantile-commercial element under feudalism, but were kept on the edges of social and economic development by discrimination and oppression. Marx is himself a product of that experience, if only in origin.

That idea of the duality of European Jewish experience with regards to the rise of capitalism, and the importance of that duality to understanding the growth of Jewish revolutionary traditions, is something I want to return to later on.

[SLIDE THREE – ELEANOR MARX]

[SLIDE THREE – ELEANOR MARX]

Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor is a key figure in British labour and socialist history, and one who I think is very often overlooked. She was centrally involved in “New Unionism”, a period of struggles in the late 1880s that reinvigorated and reshaped the British labour movement, and to which modern unions like Unite and GMB trace their origins. Eleanor in fact taught Will Thorne, a gas worker who helped found the GMB, to read.

In some ways she was a great deal more “Jewish” than her father. She was an explicit advocate for the rights of migrant workers and helped win some of the British workers’ leaders to a more supportive attitude to Jewish workers’ organisation. She was an atheist, and a secularist, and bitterly hostile to Judaism as a religion, but it’s recounted that she would often make a point of announcing herself “as a Jewess”, to confront and shake up anti-Jewish, anti-immigration sentiment that existed in the British labour movement.

Eleanor was key to developing a greater intersection and mutual support between the 1889 dock strike, in which Irish migrant workers were central, and the Jewish tailor’s strike which happened in parallel. She was elected to the Executive of the National Union of Gasworkers and General Labourers, which went on to become the GMB, and formed its first women’s branch.

In many ways Eleanor was a pioneer for both Jewish workers’ self-organisation, assisting the strikes and organisation of Jewish workers’ unions in industries like tailoring, and for the integration of Jewish migrant workers into the indigenous British labour movement.

[SLIDE FOUR – RUDOLF ROCKER]

[SLIDE FOUR – RUDOLF ROCKER]

Rudolf Rocker, a German anarchist who came to London in 1895, wasn’t actually Jewish. He’d had contact with Jewish anarchists during a stay in France, and totally immersed himself in London’s Eastern European Jewish community, learning Yiddish and living entirely as part of it. His partner was [SLIDE FIVE – MILLY WITKOP], Milly Witkop, a Ukranian immigrant and a Jewish syndicalist activist and writer.

Rudolf and Milly are excellent representatives of the incredibly febrile Jewish working-class movement that existed in London in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Working in industries somewhat on the fringes of major capitalist production, Jewish bakers, tailors, and other workers formed unions and revolutionary political organisations.

In 1884, London’s first Yiddish socialist newspaper was founded, followed the year after by the second – Arbeiter Fraynd, Workers’ Friend. Rudolf Rocker took over editorship of this paper in 1889.

[SLIDE SIX – THE LONDON JEWISH LABOUR MOVEMENT]

[SLIDE SIX – THE LONDON JEWISH LABOUR MOVEMENT]

The unions that Jewish workers in London formed were often particularly unstable, due to the extent of piecework and the precariousness conditions of employment for many Jewish workers. But the broad Jewish labour movement, in which Eleanor Marx, Rudolf Rocker, Milly Witkop, and others agitated and organised for revolutionary ideas of various kinds, was a real movement that mobilised thousands of workers.

In 1900 there were around 135,000 Jews in London, a figure that had trebled over the previous two decades. In response, the British government introduced the 1905 Aliens Act, the first ever “modern” immigration control in British history. Much of the agitation of Jewish revolutionaries concerned opposition to immigration controls, and agitation within the indigenous labour movements to see migrant Jewish workers as class brothers and sisters rather than hostile aliens.

There are myriad parallels with contemporary politics here. Immigration controls are seen as something fixed, and politics which advocate their abolition are seen as wildly fantastical. But, as I say, they date only to 1905. Immigration controls are a modern phenomenon, and the work that Eleanor Marx, Rudolf Rocker, and others did — fighting against racism, and for solidarity between migrant and indigenous worker — is very much necessary today, particularly in the context of renewed racist agitation from the right-wing media against the expected influx of Bulgarian and Romanian workers in January 2014.

[SLIDE SEVEN – NEW YORK’S YIDDISH SOCIALISTS]

All of this had very direct analogues on the other side of the Atlantic. By 1890, there were 21 Jewish workers’ unions in New York. 9,000 Jewish workers marched on May Day in 1880, many under specifically revolutionary banners calling for the abolition of wage labour.

There was a Jewish anarchist left, the Socialist Party of America – the party of Eugene Debs – had significant sections amongst Jewish immigrants, and many of the founding leaders of the Communist Party of America in 1919 – Ben Gitlow, Jacob Liebstein aka Jay Lovestone, and Alexander Bittleman – were Jewish immigrants. It is from New York’s 19th century revolutionary Jewish left that Forverts (Forward), one of the few surviving Yiddish daily newspapers, originates. It was founded 1897 by supporters of the Socialist Labor Party, including Abe Cahan (above, left), who came from a rabbinical family in Lithuania but who studied Russian language and secular politics in secret.

The two figures on the left of the slide journeyed out of revolutionary politics into more mainstream leftisms, while Rose Schneiderman (above, right) remained within “official” communism, what I would call Stalinism.

That taints her legacy somewhat in my view, but she deserves to be remembered for her heroic work as an organiser of women garment workers – that is, sweatshop workers – and particularly her role in the aftermath of the famous Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire in which 113 workers died in what was, until 9/11, the worst workplace disaster in American history.

The conditions of Jewish economic and social life in New York and London (and other cities, although these two are archetypical) were in some ways replications of the lives they’d led in the Pale – bunched together in tight-knit communities on the edges of the centre (London’s East End, or New York’s Lower East Side), engaging in wage labour but in industries somewhat liminal to major capitalist production.

[SLIDE EIGHT – JEWISH ANARCHISTS]

With the exception of Rudolf Rocker and Milly Witkop, most of the people we’ve met so far are “classical”, if you like, Marxian socialists. But Jews were prominent in the leadership of Europe’s class-struggle anarchist movements, including anarcho-syndicalists like Rudolf Rocker and the arguably more famous Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. I’m not intending to dwell on them, although Berkman’s personal background is worth a word – his father was a successful and aspiring businessman who, because of his success and his connections, was granted the right to move from the Pale of Settlement, so Berkman actually grew up in Saint Petersburg. That experience is obviously exceptional but in a sense is quite an accelerated, or perhaps distilled, version of that dynamic of duality I referred to earlier.

At this point I also want to say a word or two on Jewish revolutionaries’ engagement with organised religion and the synagogues. I mention it under the heading of the anarchists because they were perhaps the most explicitly anti-religious, anti-theist element, and the most extravagant in their anti-religious agitation and atheist propaganda. Yom Kippur Balls, irreverent parties on the Day of Atonement, were a feature of radical Jewish life in both London and New York, and there are stories (possibly apocryphal, although I hope not) of Jewish anarchists organising “ham sandwich parades” to mock and deride the piety and dogma of the faithful.

The role of the synagogues and the official Jewish establishment in relation to revolutionary politics is not an honourable one, in my view. In 1936, the Jewish Chronicle and the Board of Deputies counselled Jews to stay at home when Moseley’s fascists planned to march through the Jewish East End. Fortunately, a rather large number of people ignored them.

That aspect of Jewish revolutionary life, of being entirely, profoundly Jewish – in terms of one’s ethnic and cultural identity, milieu, and experience – but also entirely hostile to religion, and to the cross-class politics of the religious establishment, is another of the fascinating dualities, or tensions, within this history. That tension was, in different ways, quite key to the experiences of our next two characters, perhaps two of the most famous Jewish revolutionaries.

[SLIDE NINE – ROSA LUXEMBURG] & [SLIDE TEN – LEON TROTSKY]

Rosa Luxemburg, one of the key leaders of the revolutionary German workers’ movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s, and Leon Trotsky, the architect of the Russian revolution and its survival through the ensuing civil war.

Like Marx, their process of engagement with revolutionary politics was a process of breaking from Jewishness rather than consciously taking their own Jewish experience as a point-of-departure or foundation stone in their politics. But, just as Marx’s Jewishness did shape his experience and thought in ways we’ve discussed, so too for Luxemburg and Trotsky.

Luxemburg was born in Zamość, which has quite interesting Renaissance origins but had been part of the Pale of Settlement, but moved to Warsaw where she was educated. Her grandfather, like Marx’s father, had broken a long tradition of Orthodox Judaism in the family and was a pro-enlightenment secularist. Her grandfather and her father were involved in reform movements with Zamość’s Jewish community, and while they were assimilationists who encouraged their children to think of themselves as Polish rather than Jewish, Rosa’s early experiences were of struggle within the Jewish community but against Jewish orthodoxies and Jewish separatism. I recommend the excellent essay “You Alone Will Make Our Family’s Name Famous”, by Luxemburg scholar Rory Castle, which discusses precisely this question of Luxemburg’s Jewish identity.

Trotsky’s relationship to his own Jewishness is also an essay-worthy subject. His family was well-off, so his day-to-day life as a young man was not that of the Jewish proletarian in the Pale. Trotsky was an opponent of Zionism, and of left-wing Jewish cultural autonomism (Bundism), but his views on this question shifted and changed throughout his life. Towards the end of his life he reconciled to the view that Jewish autonomy or nationhood in some form was, if not desirable, probably inevitable, but that under capitalism any such autonomy or nation would be unstable and prey to reactionary manipulation by imperialist powers. Trotsky’s experience is also a particularly Jewish one in that his Jewishness became one of the major motifs of the Stalinists slanders against him, as Stalinism hardened up into a more-or-less explicitly anti-Semitic ideology, at least at the level of state power in Russia.

[SLIDE TWELVE – BER BOROCHOV]

[SLIDE TWELVE – BER BOROCHOV]

I want to talk now about two other important revolutionary traditions, which existed in parallel with the ones we’ve looked at so far, and often intersecting with them, but as distinct tendencies. In a sense I’ve done a disservice by arriving at them relatively near the conclusion of my talk because they are the two traditions of revolutionary politics which are specifically, explicitly “Jewish”. So I want to talk a little now about Bundism, socialist Jewish cultural autonomism, and first, the revolutionary socialist-Zionism of Ber Borochov.

Borochov, who founded Poale Zion, represents the left-wing extremity of historical Zionism. He saw the Zionist project not in religious terms but as a necessary response to capitalism, which he saw as keeping Jews in a permanent state of transience and migration. He advocated that Jewish workers should emigrate to Palestine, unite in common organisations and struggle with the Arab workers, and construct a socialist state. Borochov supported the 1917 revolution, and a socialist-Zionist detachment fought for the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War.

Although left-wing variants of Zionism remained fairly prominent, Borochov’s explicitly revolutionary, Marxist Zionism was sidelined fairly early on and he is not an especially well-known or remembered figure. He’s also somewhat idiosyncratic in that he was an advocate of Yiddish, which most Zionists regarded as innately diasporic.

[SLIDE THIRTEEN – THE BUND]

[SLIDE THIRTEEN – THE BUND]

Leftist Zionists clashed with assimilationists who advocated that Jews should integrate into the workers’ movement of whichever country they found themselves in. But there was another tendency, which rejected both the nationalism of Zionism and absolute assimilation – the General Jewish Labour Bund, founded in Vilnius in 1897. (The photo is from an event celebrating its 30th anniversary.)

The Bund was Marxist, but advocated Jewish cultural autonomy within the countries and movements where they found themselves, united by the transnational Bundist party.

Bundism was a mass force in Europe, representing tens of thousands of Jewish workers, and its history is a profoundly rich one. It is internally politically diverse, evolving left and right wings divided over questions such as what attitude to take to the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik government.

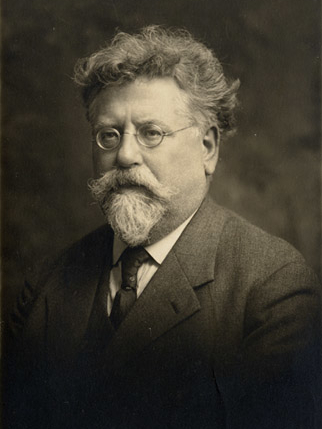

[SLIDE FOURTEEN – VLADIMIR MEDEM]

[SLIDE FOURTEEN – VLADIMIR MEDEM]

Vladimir Medem, the founding theorist of Bundism, was an opponent of Lenin with the international socialist movement. Many Bundists supported the Mensheviks, the Russian revolutionary left’s more conservative party, but some, like this woman…

[SLIDE FOURTEEN – KHAYE-MALKA LIFSHITS, aka ESTHER FRUMKIN]

…didn’t. This is Khaye-Malka Lifshits, also known as Esther Frumkin. She’s quite a heroic figure, who was imprisoned for her revolutionary activity and who, in 1920, was involved in a left-wing split from the Bund of activists who wanted to affiliate to the Bolshevik’s newly-founded Communist International, known as the “Third International”. The organisation she founded, the Kombund, did affiliate to the Third International and retained an autonomous identity as the Central Jewish Bureau within the Communist Party of Poland.

She was a passionate Yiddishist and wrote extensively about Yiddish. She was arrested by the Stalinist regime in 1938 and died in 1943 in a Stalinist labour camp in Karaganda, in what is now Khazakhstan. The Stalinist regime denounced “unreconstructed Bundists” as “counterrevolutionary nationalists”.

Contemporary organisations like the Jewish Socialist Group identify with the Bundist tradition. Bundists were also particularly active in pioneering the Workmens’ Circles, the Arbeiter Rings, founded in 1900, as mutual aid societies and cultural committees which became forums, and indeed terrains of ideological struggle, for Jewish revolutionaries from a range of backgrounds. The official Arbeiter Ring organisation still exists today, although in a much depoliticised form.

[SLIDE FIFTEEN – JEWISH “THIRD CAMPISTS”]

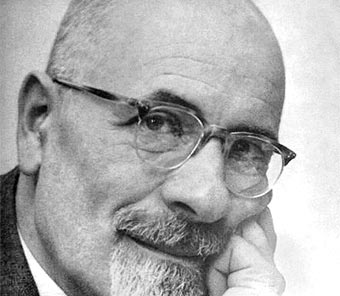

I’ve included these three as a bit of a footnote, and from personal bias. These are three key figures in the particular political tradition I belong to, sometimes called “third camp” socialism which originated in the 1940s as a radically anti-Stalinist tendency that pioneered the slogan “neither Washington nor Moscow”. Max Shachtman (above, left), Hal Draper (above, centre), and Phyllis Jacobson (above, right) were all veterans of the American far-left and all emerged from New York’s Yiddish-speaking, Jewish immigrant left – in Shachtman’s case as a first generation immigrant.

Shachtman was, in 1929, one of the founding fathers of American Trotskyism, and was particularly active in opposing Stalinist anti-Semitism. When the great fissure between Stalinist and anti-Stalinist Marxism occurred in the mid-1920s, many Jews, both in the Soviet Union itself and internationally, remained “loyal” to the Russian regime and became Stalinist. But I think the historical record shows clearly that Stalinism was an anti-Semitic ideological force on a whole variety of levels, and I wanted to flag up these individuals to emphasise Jewish involvement in the attempt to rescue a radically-democratic, internationalist conception of Marxism from the muck heaped on it by Stalinism.

These Jewish revolutionaries are also significant in generational terms. In different ways they were all involved in America’s civil rights movement and the New Left of the 1960s, and although the discrete, Yiddish-speaking, Jewish revolutionary culture we’ve been talking about today was then much diminished, people like these three represented a living link to it, even thought they had quite different political journeys – Shachtman becoming a Cold War liberal, while Draper and the Jacobsons remained active revolutionaries.

We’ve met a handful of individuals here. I chose them because I think they are representative either of particular traditions within Jewish revolutionary politics, or because they are representative of a specific historical moment in terms of Jewish political experience and organisation, or both.

Their views, and experiences, are all very different. For many of them, the process of their becoming revolutionaries was about explicitly breaking from Judaism, and what they saw as reactionary and backwards in Jewish religion and cultural. The extent to which they broke from, or abandoned, their Jewishness, if such a thing is possible, varies, and all were involved in debates about assimilation, autonomy, nationalism, and so on. For Bundists and Ber Borochov’s Marxist-Zionists, their epochal task was to develop revolutionary conception of Jewish nationhood, expressed either as cultural autonomism or as nationalist aspiration.

They express the diversity and plurality of the history of Jewish engagement with and production of revolutionary ideas, and I think it would be unjust and reductionist to try and collapse them all into an undifferentiated, homogenous “Jewish” experience.

But I think we can tease out from their varying experiences some common threads, and I want to leave you with these are concluding thoughts.

Jewish revolutionaries and revolutionary movements have shared an intensely literary character. There have been many heated debates within the movements we’ve talked about on the topic of language, and all the movements were great producers of literature – in the form of newspapers, pamphlets, and books – themselves. I think that emphasis on the literary, on written exchange and debate, is something which has been an integral element of Jewish culture historically. It’s something which I think Jewish enlightenment philosophers brought to their period and something which is picked up again by 19th and 20th century Jewish revolutionaries.

Fundamentally for me, however, the relationship between Jews and revolutionary politics does have its roots in material historical experience. But it’s not merely that Jews are amongst history’s most put-upon, subjected, and brutalised people. I think it would be vulgar determinism to suggest there’s an automatic, causational link between brutalisation and immiseration and the development of revolutionary consciousness. There’s plenty in history that rather suggests the opposite.

Rather, I think the roots of the great tradition of Jewish revolutionary culture lie in the quite specific role we have played in the development of European capitalism. Forced into being an incipient mercantile element in feudal society, Jews were at one in the same time integral and liminal. We were essential to commercial and economic functioning, and hence the development of capitalism, but also excluded from it – socially and ideologically, because of racism and oppression, by quota laws, by pogroms, and geographically, often living in communities literally on the edge of developing settlements that grew into capitalist towns, or effectively exiled and hemmed-in altogether in the Pale of Settlement. The dialectical character of historical Jewish experience, simultaneously inside and outside the development of modern capitalism, is an experience of societies in motion and transition, and creates the potential for a universal-historical perspective, which is the essence of any revolutionary politics.

I give the last word to Isaac Deutscher (right) – which I’m somewhat loathe to do, because I think the totality of Deutscher’s political legacy is a negative rather than positive one. But on this topic I think he is a genuine source of light. In his book on this subject, he posits the concept of “the non-Jewish Jew” – the individual whose experience is shaped fundamentally by their Jewishness, but who uses that experience to aspire to a universal, rather than a solely “Jewish”, worldview, a worldview which may in part be shaped by kicking back against, critiquing, and breaking from what they perceive as reactionary religious or cultural dogmas within their Jewishness.

I give the last word to Isaac Deutscher (right) – which I’m somewhat loathe to do, because I think the totality of Deutscher’s political legacy is a negative rather than positive one. But on this topic I think he is a genuine source of light. In his book on this subject, he posits the concept of “the non-Jewish Jew” – the individual whose experience is shaped fundamentally by their Jewishness, but who uses that experience to aspire to a universal, rather than a solely “Jewish”, worldview, a worldview which may in part be shaped by kicking back against, critiquing, and breaking from what they perceive as reactionary religious or cultural dogmas within their Jewishness.

Deutscher writes:

“Have they [Jewish revolutionaries] anything in common with one another? Have they perhaps impressed mankind’s thought so greatly because of their special ‘Jewish genius’? I do not believe in the exclusive genius of any race. Yet I think that in some ways they were very Jewish indeed. They had in themselves something of the quintessence of Jewish life and of the Jewish intellect. They were a priori exceptional in that as Jews they dwelt on the borderlines of various civilizations, religions, and national cultures.

“They were born and brought up on the borderlines of various epochs. Their minds matured where the most diverse cultural influences crossed and fertilized each other. They lived on the margins or in the nooks and crannies of their respective nations. They were each in society and yet not in it, of it and yet not of it. It was this that enabled them to rise in thought above their societies, above their nations, above their times and generations, and to strike out mentally into wide new horizons and far into the future.”

The “quintessence of Jewish life” is, on the whole, very different now. But our world, like the world of the Jewish proletarians and proto-proletarians of the Pale, is still a world wracked by exploitation and oppression, and it is to that revolutionary universalism, and that desire for totalising, universal, systemic change, to which I believe we, as Jews, should still aspire.

Your slide five, labeled Milly Witkop, is Emma Goldman. Milly is here http://www.ephemanar.net/imagesdeux/rocker_millie.jpg