How the Terms We Use Don’t Describe What we Really Think

British Jews are Zionist. Everyone knows this. All the major Jewish institutions declare themselves Zionist, along with all the youth movements. Zionism is what we do, what we are, end of story. But do we really know what this means? Zionist hegemony in British Jewry is so unchallenged that it is rarely unpacked as a term, its meaning poorly understood. This came to a head when, in the wake of the Paris and Copenhagen attacks, various Israeli officials, including Netanyahu, called on British Jews to make aliyah.

Many ‘prominent’ Jews and Jewish organisations took umbrage at this, considering it highly presumptuous. In a fascinating Newsnight debate in February, David Ceserani politely pointed out that European Jews are rooted in the countries where they live, where they have built rich Jewish lives, and argued that Europeans stood shoulder to shoulder with Jews when they are attacked. Ceserani suggest that Israel was attempting to incite immigration out of fear, implying that this had more to do with Netanyahu’s domestic agenda than it did with concern for the safety of European Jews. Speaking from Jerusalem, Dore Gold, somewhat surprised to be faced with Jewish dissent on this issue, pointed out that Netanyahu, was simply reiterating a key Zionist value – that Jews should come to Israel Why should this be controversial? ’You are welcome to come home!’ thundered Gold, in a booming tone. ‘This has been the message of Zionism since Theodor Herzl saw a need for it back in the 19th century.’

Gold had a point. Negation of the diaspora, and a belief that Jews should come to Israel has been central to (most) Zionist thinking, and certainly after the foundation of the state in 1948. This is a part of the picture that British Jews tend to play down, finding it distinctly embarassing. We are proud British citizens, we are tremendously rooted in, and loyal to the UK. Sometimes our children decide to make aliyah, and we feel torn, we know that in some sense they are doing the ‘right thing’ but we would also like to have them stay near us and mourn the loss to the UK’s Jewish community. Rhetorically we sometimes say that Israel is home for the Jews but we’re not quite sure we mean it. The UK certainly feels like home for most of us. So when British Jews call themselves Zionists they don’t quite mean what Dore Gold and Benjamin Netanyu mean. There’s a different definition at play, just as, I believe there is for many Jews around the world who pronounce themselves Zionist but are committed to remaining where they are and leading full Jewish lives in the places in which they reside.

It seems that many diaspora Jews use the word Zionist to mean something like this: we are proud Jews and not ashamed of our identity. We are committed Jews but not necessarily religious, we self-define as members of the Jewish people despite not living in the Jewish state. We think Jews should be able to run their own affairs, and pass on Judaism through language and culture. We identify and care deeply about the welfare of Jews around the world, be they in Israel, American or Europe. It’s a version of Louis Brandeis statement: “to be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists”.

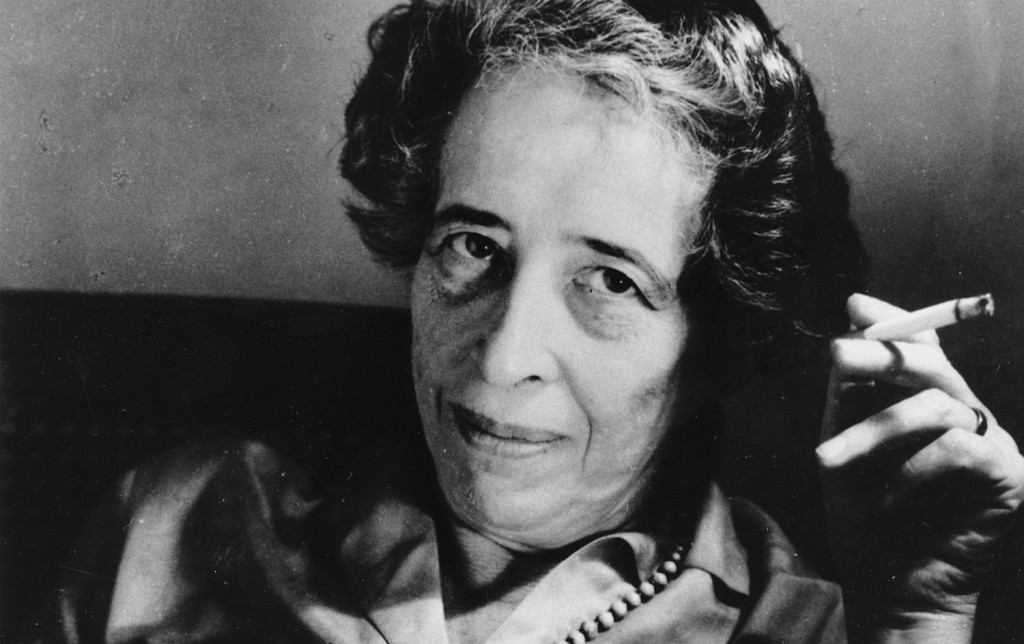

This loose usage of langauage wouldn’t be a problem if it wasn’t for the troubling fact that some pretty contentious (to say the least) acts are taken out in the name of Zionism. House demolitions, expulsions, wars, discriminatory law and the ongoing military occupation have all been justified by the cause of Zionism, due to the need to maintain a Jewish majority, even if such actions would have horrified at least some pre-state Zionist thinkers. As a result, there is a growing move within the Palestinian solidarity movement to make Zionism a word like apartheid – a word that means racism and ethnic cleansing rather than simply a banner under which unjust acts have been carried out. While this is in some sense a progressive move – distinguishing between Judaism and Zionism and blaming the latter rather than than the former, it has a few awkward side effects. Firstly, the implication that Zionism is always racist is strangely essentialist – political movements change pretty radically over time – what they are at one moment does not define how the will be at another. Secondly, it’s historically dubious: plenty of pre state Zionist thinker (Kohn, Ahad Ha’am, Rawidowicz, Buber, Arendt etc.) did not support a sovereign Jewish state, instead advocating for a self governing Jewish collective in Palestine, alongside an Arab collective, both under British mandate rule. Such Zionism, due to not requiring a Jewish majority, would not have required the kind of ethnic cleansing and discrimination that later statist Zionism was guilty of. Thirdly, and most problematically, the move to brand Zionism an unacceptable term brands Jews who call themselves Zionists (often for the very loose reasons laid out above) politically beyond the pale. So when pro-Palestinian activists go out of their way to distinguish between Jews (good) and Zionists ( bad) they end up alienating the vast majority of Jews who call themselves Zionists even if they reject many of the oppressive policies that anti-Zionists see as essential to Zionism.

The fact that many Jews continue to call themselves Zionist despite, whilst disagreeing with some of its fundamental tenets and whilst not necessarily being supporters of racism and ethnic cleansing may be connected to the lack of an alternative. If you are not a Zionist what can you be? You can be an assimilationist, one that ceases to call yourself a Jew but instead melds in with the rest of the population. That doesn’t sound too attractive to those who want to continue to have some kind of ongoing Jewish or identity. Or you can be purely a religious Jew, focusing entirely on God, prayer, Torah and halacha. But if you just don’t believe in God, and for your Judaism is more cultural than thesitic this doesn’t sound like a great path either.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was an alternative – a way to live a rich Jewish life that is not exclusively religious that doesn’t imply that you support supression of the Palestinians and thus set you at odds with pretty much all progressive people everywhere? Fortunately there is, it’s just that no-one ever tells you about it. It’s been called many things – autonomism, non-territorialism, autonomy, diaspora nationalism. It has had support across modern Jewish politics – amongst Bundists, liberals, autonomists and Zionists. It holds that Jews constitute a nation just like other nations. It agrees that nations should be able to run their own affairs, promote their own language and culture etc. It just doesn’t agree that nation = territory. The right to self governance, to have autonomy, doesn’t imply the right to exclusive control of territory (where, inevitably you find other people in your way). And this right can be exercised wherever Jews find themselves – allowing for the creation of multiple centres of Jewish life rather than just one centre and a periphery. This approach already sums up the way many diaspora communities operate, with Jewish schools, welfare institutions and cultural organisations constituting a rich, and quasi-autonomous Jewish life, without the need for any overarching ‘Jewish state’ . But it could also describe how Jews in Israel could constitute themselves in a more just future; when discriminatory laws have been abolished and when the state becomes a state of all its citizens rather than an ethnocracy. Just as Jews in mandate Palestine had a self governing community (with schools, hospitals, internal elections) while overall control of the territory remained in the hands of the British, a future UN led/power sharing government could take control and guarantee equality for all, whilst allowing the Jewish and Palestinian communities to be non-territorial collective entitites that manage their own affairs in the spheres of culture, education, language and religion. Whether in Israel or the diaspora (terms we should start to rethink) secular, Jewish collective life could be separated from the discrimination and domination that inevitably occurs when an ethnic group seeks exclusive control of a given territory.

This is the sort of work we need to do to encourage Jews to move away from support for oppressive, statist nationalism – to provide an alternative that doesn’t sound like a thinly veiled version of assimilation or a call to become a purely religious sect. Could the vision laid out above be called Zionism? Not by the standards of the strand of statist Zionism that has become hegemonic since 1948. From that viewpoint it would be capitulation. But from the position of earlier Zionist thought it would seem to be a fulfillment of the movement – it would, after all, involve a substantial number of Jews living in the area described by the bible, speaking hebrew, with Jewish schools, universities and theatre. I think we can assume Ahad Ha’am would have approved. And all of this could continue without the need for a Jewish majority in the territory, the single idea that has necessciated explusions, occupation and ongoing war. I think many who currently define as Zionist would be happy to call that Zionism.

None of this should be seen as an apologetic for the way Zionism has operated in Israel since the formation of the state – as a system of ethnocracy, a system of running the state in the interests of just one ethnic group. But the project now is to unpick that system without denying the legitimate desire for Jewish collective autonomy, wherever Jews find themselves. We need to change our language – diaspora Jews should be more aware that when they declare themselves Zionists they sound to many as if they are apologists for ethnic cleansing and discrimination, while pro-Palestinian campaigners should be aware that claiming that Zionism always was, and always will be oppressive can sound to Jewish ears as if there is no acceptable Jewish path outside assimilation or a purely religious identity (a la Satmar and Neturei Karta). This work might sound like navel gazing – putting the oppressor on the couch while Palestinians continue to suffer every day. But this project is in fact essential – Jews will become full allies in the battle for justice in Israel/Palestinian only when they see that living a secure, rich, full Jewish life does not depend on oppressing another people.

Thanks for this thoughtful writing, it’s an interesting project! Could you point some source references for non statist Zionism please?

I struggle with calling contemporary Jewishness which is non satist, Zionism, and think there are alternatives besides ‘assimilation’ and Zionism.

It seems to me that most jewish people, orgs, media which identify as Zionist do support the Zionism we have seen in action in pre and post state.

Also, this yid is not a proud british citizen, though technically a citizen and a Brit x

There are certainly alternatives besides assimilation and Zionism (as it is usually understood) – but I would argue they are all some form of autonomism – where Jews are able to live a full, quasi-autonomous Jewish life without being in a Jewish state. I think this is how the healthiest Jewish diaspora communities operate. As to what most Jewish people who call themselves Zionists support – well sometimes the things they support in a knee jerk, defensive way don’t tally with the values they really hold. Part of the idea of this discussion is to separate those who really are apologists for war and ethnic cleansing from those that just want to perpetuate Jewish life and haven’t (yet) appreciated that there are other ways to do it. As to resources – to start you off http://www.amazon.com/Between-Jew-Arab-Rawidowicz-Institute/dp/1584658541 http://www.amazon.co.uk/Zionism-Roads-Not-Taken-Rawidowicz/dp/0253221846, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brit_Shalom_(political_organization) http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Kohn_Hans http://www.zionism-israel.com/dic/Autonomism.htm http://www.tikkun.org/nextgen/how-hannah-arendt-was-labeled-an-enemy-of-israel-email-article-to-a-friend

“Zionism” as it is usually understood? By who? Those who are for it (in which case it means the Jewish movement for safety and independence), or those who are against it (the Jewish conspiracy to dominate the world and kill people, especially the Palestinians, just because it’s fun)?

For me the best example of the contradictions here is Maccabi, the jewish sports organisations founded in Europe (quickly spreading to communities as far from each other as Baghdad and Berlin) at a time when jews were banned from many goyish sports clubs but also because they wanted to have modern secular ways of expressing their Judaism. They have from their inception been intertwined in complex ways with pre and post 1948 Zionism- not least because of the ways in which Maccabi in name and spirit both endorses and is contradistinction to the sabra idea of muscularity in Zionism. Today pretty much all Maccabi clubs are ‘Zionist’ but they simultaneously represent the potential for other types of jewish autonomy as Jews of many types compete representing their diaspora community. ‘Israel’ is just another team on the field – Maccabi tel aviv vs macabbi london would be a hard fought game. The European Maccabi games next month in Berlin will be a magnificent display of all these contradictions and most attending won’t be conscious of it – I’ll be there in disguise trying to expose the contradictions

I have a problem with the semantics. Zionism TODAY, in English and other languages as they are spoken, denotes a specific relationship with a country called Israel. If people call themselves Zionist, even when living a full rich life in the diaspora, to me it betokens a positive view of Israel as Jewish, even if it were a ‘state of all its citizens’ with all its different groups having autonomy over their respective affairs. In any case, people who are certainly not Jews (let’s not get into identity questions) will, I believe, think in this way, especially if there is a Christian background. Again, not a question of religious belief, but culturally, ‘Zion’ is now seen as that country over there called Israel. So I would drop the ‘Zion’ bit. I don’t see why one can’t support the idea of a country called Israel and yet not be ‘Zionist’. I don’t see why, living my full life in the diaspora, I can’t just be me, without all the wretched labels.

Hi, do you not have a Spellcheck? I’m a proofreader and would love to proofread your material before it goes to Web – for free. I have just come across your website and really enjoyed what I’ve read so far. I have a lot of spare time. Thanks in particular for the above article.

some 100 years ago there jews who were: *Zionists* (definition: solve “the Jewish problem” [victims of antisemitism] by creating a homeland for the jews), *anti-Zionists* (Bundists who believed that the Jewish communities should have cultural authonomies wherever Jews live, Orthodox Jews who thought a homeland, cenrtainly a state, must be the work of god), *territorialists* (creating a (political, i.e. state) homeland for the Jews, but not in Zion) and those who had *no opinion* on the matter (which were the majority of the Jews at the time).

In the 1930s things have changed, as we all know. This was also a time when one could ralise that leaving the “rule” to the Brits for example, had a strong down-side. Jewish refugees were not alowed in the Jewish homeland, nor elsewhere. We all know what the result of this was. AND this is the reason so many Jews nowadays regard Israel differently: “If things go wrong in the place I live now, there is always a place for me to flee to”. In my humble opinion this is the reason so many Jews are hesitant to be critical of Israel, being aware of the fact that they do not carry the burdon of defending the Jewish state.

A 100 years later we still have: Zionists (who have, just like 100 years ago, a big variaty of ideas about how to implement the idea. This is the majority of the Jews nowadays, and I think my comment above about the need to escape is significant here. This is not implying they feel they ought to immigrate to Israel. ), anti-zionists (Orthodox, but also local Jews in different countries, The Bundists do not belong to this group any more), *no-opinion* (this group has shrinked significantly). The Bund is no more anti-Israel. It still believes Jews should have cultural autonomy wherever they live. Including Israel. And, many Bund groups in the world are critical about the Israeli politics, just like many Israeli’s are. A new group in the list are the * Post-Zioninsts*. The understand that the state of Israel is a fact, many of them live there. They have other (different) political views.

To me this is the most important: Israel is an existing state; all solutions to the conflict only make sense when accepting this fact. And it is up to both People in the area to find a solution that suits them. I believe that, providing the ‘Zeit geist’ which is very nationalistic, and religousely un-inclusive, a separation between the group is the only realistic solution. I hope, and dream, that a confedferation, open borders, and even more progressive constructions, will be feasible in the future. In other words: the only feasible solution provided the situation now is the Two-stat solution.

As for the diaspora Jews. I hope Netanyahu stops calling us all to immigrate to Israel, and I hope even more that we, in the different ‘diaspora’s’ work hard to give meaning to being (non-religous) Jews as a community, other than Post-Holocaust trauma’s or Pro/Anti-Zionism. The ideas of the Bund could be a good starting point. What we should NOT do, is feel we HAVE to develop a position in regards to Israel. This should NOT define our Jewish identity, there is no reason to demand Jews abroad to have an opinion about Israel, just as well as nobody should demand they have an opinion about another country than the one they live in.